Does deodorant cause breast cancer? Can wearing an underwire bra increase your breast cancer risk? What about squeezing your breast?

We dispel 10 common myths about breast cancer causes.

1. Deodorant

2. Underwire bras

3. Breast injury

4. Stress

5. Nipple piercing

6. Mobile phones

7. IVF

8. Abortion

9. Chemicals in the environment

10. Night shifts

1. Does deodorant cause cancer?

Using deodorant or antiperspirant does not cause breast cancer.

Claims that deodorants or antiperspirants increase your risk of breast cancer have been around for several years.

Some people have also claimed that aluminium in antiperspirants can increase your risk.

However, there’s no convincing evidence of a link between breast cancer and deodorants, antiperspirants or their ingredients.

2. Do underwire bras cause breast cancer?

Underwire bras do not increase your risk of breast cancer.

There have been some concerns that the wires in the cup of underwire bras may restrict the flow of lymph fluid in the breast causing toxins to build up in the area. However, there’s no reliable evidence to support this.

If your bra is too tight or too small, the wires can dig into your breasts and cause discomfort, pain or swelling. Find out more about wearing a well-fitting bra.

3. Can squeezing or being hit in the breast cause cancer?

An injury, such as falling or being hit in the chest, will not cause breast cancer. Squeezing or pinching the breast or nipple will not cause breast cancer either.

It may cause bruising and swelling to the breast, which can be tender or painful to touch.

Sometimes an injury can lead to a benign (not cancer) lump known as fat necrosis. This is scar tissue that can form when the body naturally repairs the damaged fatty breast tissue.

4. Does stress cause cancer?

There’s no conclusive evidence that stress increases your risk of breast cancer.

A number of studies have looked at the links between stress and breast cancer, but there isn’t enough evidence to show a clear association.

Stress can be linked to a rise in other lifestyle behaviours, such as being less active or drinking alcohol, which could increase your risk of breast cancer.

5. Can nipple piercing cause breast cancer?

Nipple piercings have become a popular trend. But there’s currently no evidence that having pierced nipples increases the likelihood of developing breast cancer.

However, the area pierced is at risk of infection, at the time of the piercing and as long as you wear the jewellery, possibly even longer.

6. Do mobile phones cause breast cancer?

There’s no evidence that radiation from mobile phones has any effect on your risk of developing breast cancer.

Some people worry that radio waves produced and received by mobile phones may be a health risk, especially if they keep their phone in their breast pocket.

However, there’s currently no evidence that radio waves from mobile phones cause breast cancer or increase the risk of developing it.

7. Can IVF cause breast cancer?

There’s no evidence that having IVF (in vitro fertilisation) treatment affects your risk of breast cancer.

Current evidence suggests women who have received IVF treatment are no more likely to develop breast cancer than women who have not had IVF. However, IVF is a relatively new procedure and more research is needed to be sure of all the long-term health effects.

8. Does abortion increase the risk of breast cancer?

Having an abortion does not affect your risk of developing breast cancer.

Some previous research on abortion suggested it might increase your risk of breast cancer. But several well-designed studies from recent years have shown this is not the case.

9. Can chemicals in the environment cause breast cancer?

There’s no conclusive evidence that exposure to chemicals in the environment increases your risk of breast cancer.

Lots of studies have looked at the relationship between breast cancer and chemicals in the environment such as pesticides, traffic fumes and plastics, but there’s no clear evidence of any links.

It can be very difficult to work out the effects of individual chemicals when we are exposed to low levels of thousands of chemicals during our lifetime.

Some studies have suggested that women who are exposed to chemicals in their jobs, for example in the manufacturing industry, may be at higher risk of breast cancer. But the evidence is weak and more research is needed. Employers are legally required to limit exposure to chemicals that may cause cancer.

10. Can working night shifts cause breast cancer?

Although it was previously thought working night shifts may increase breast cancer risk, the latest research has found people who work night shifts are at no greater risk of breast cancer than those who don’t.

This is the case regardless of the type of work and the age someone starts night shifts.

Malignant breast tumours are the leading cause of death from cancer among Latino women and the second most frequent cause of death among American women [1,2]. In Brazil, more than 57,000 new cases are estimated per year, with 13,345 deaths [3]. This disease is heterogeneous, and several environmental and genetic factors are involved in its aetiology [4]. Changes due genetic mutations account for a minority of cases; the majority of cases are due to sporadic causes [5-7]. The well-known epidemiological factors associated with breast cancer are the behavioural and hormonal factors, such as early menarche, low parity, late menopause and the use of hormone replacement therapy [8-11].

Alcoholism, obesity, and smoking have also been implicated [12-14]. However, these factors do not explain all cases, as they are highly variable depending on the population studied [15]. Despite all of the studies on this topic, the causes that lead to breast cancer are not yet fully understood. Some unknown triggers exist that lead some women to develop the disease while others – who have absolutely identical living conditions – do not develop it. There is persistent questioning regarding bra use and increased risk of breast cancer; however, to date, studies on this topic have been inconclusive. Recently, it was demonstrated that the number of hours wearing a bra was not associated with disease in postmenopausal women [16]. However, Hsieh et al . demonstrated that premenopausal women who did not wear a bra had half the risk of developing breast cancer compared with bra wearers [17]. Although the time of wearing a bra and the bra cup size had been investigated in relation to breast cancer the stretchiness of the bra never went evaluated before. The present study measures in loco the bra stretchiness needed to fit a woman's chest (stretch percentage) multiplied by the number of daily bra wearing hours in patients with breast cancer and compares the results with the ones obtained from control women without the cancer

This study was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the University of Brasilia (Universidade de Brasília) Medical School. Patients who agreed to participate signed an informed consent form. This case-control study included 304 patients. For this evaluation, preand postmenopausal patients of the Mastology Outpatient Clinic of the University of Brasilia Medical School who had a diagnosis of breast cancer by histopathology examination were selected as cases. The controls were patients of the general gynaecology outpatient clinic of the same university without breast cancer confirmed by clinical and/or image examinations. The study included only bra-wearing patients who were wearing a bra on the interview day. These data were collected during the consultations, and the questionnaires were answered during a personal interview with consecutive patients that were scheduled for that day. All patients were matched by age as all of them belonged to a low socioeconomic level, had a low educational level and mixed ethnicity because these are the characteristics of the population treated by the Service. Several covariates considered as potential confounders, such as age at menarche, parity, breastfeeding, menopause, age at menopause, use of hormone replacement therapy, body size, family history of breast cancer, alcohol consumption and smoking was also evaluated.

The participants were asked about specific information on their bra - wearing habits, such as the age they began to wear bras, the type of bra worn throughout life and if they wore a bra when sleeping. After collecting the data, the bra’s features, such as the presence/absence of a metal underwire and the type of fabric, were evaluated.

Next, the bra band was measured (centimetres) with a measuring tape. This part of the bra was measured because it is the part that holds the bra to the body and carries most of the weight of the breasts [18]. The measurement of the band bra stretchiness was obtained as follows: the bra diameter (BD) was measured when the patientwas not wearing the garment and without stretching its lower edge. Next, the patient’s chest diameter (CD) was measured at the line left by the band bra.

The difference obtained was then divided by the band bra measurement without any stretching and multiplied by 100 to obtain the stretch percentage of the bra. For example, if a bra measured 80 cm without any stretching while the patient’s chest measured 88 cm, then the bra stretched 8 cm to fit the patient. Next, the following calculation was performed: 8/80=0.10 x 100=10%, which represented the stretch percentage, which, in this example, was 10%. The time of bra use in hours (Th) was obtained by asking the patient how many hours per day and how many days per week she wore a bra; a daily mean bra-wearing time was thus obtained. The following formula was used to calculate the bra stretch percentage multiplied by the wearing time, (SxT): SxT=((CD-BD)×100 )/BD X Th

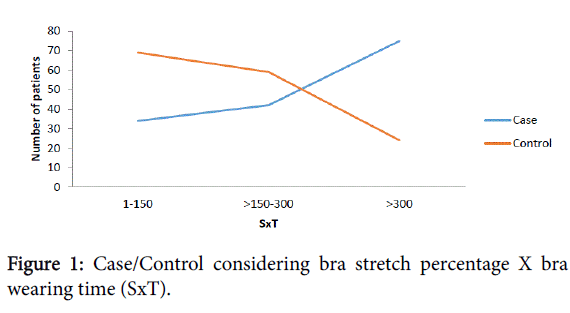

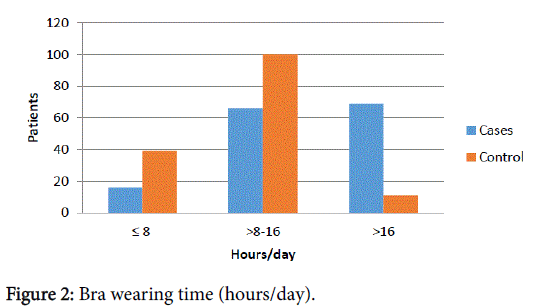

The diameter of the bra band was divided in half. The Stretchiness X Time (SxT) and Time in hours (Th) data were divided into 3 parts. Importantly to observe that while increase SxT or Th, increased the number of patients with breast cancer and decreased the number of patients without breast cancer and vice versa. There including a transition area where the data that was crossed (DXT 150-300) (Figure 1) and (Th 8-16) (Figure 2).

Statistical Methods

Data were compiled and analysed using the program SAS version 9.3 (NC, USA). Multivariate analysis was conducted using a Poisson regression with robust variance (log-linear). Three multivariate models were used separately, one for each independent variable of interest; prevalence ratios with 95 % confidence intervals were calculated to examine the strength of the association between the occurrence of breast cancer (dependent variable) with the bra stretch percentage, bra-wearing time multiplied by the bra stretch percentage and the brawearing time (independent variables of interest) adjusted using a set of demographic, behavioural and clinical covariates.

In these models, after initial crude analysis, the covariates having associations (p<0.25) with the occurrence of breast cancer were included with the independent variables and then adjusted [19]. The Poisson regression was used because it provides a better estimate of the prevalence ratios, which in turn more significantly represent the effect measures for cross-sectional studies [20]. The level of significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

The patients ranged from 24 to 92 years old. Infiltrating ductal carcinoma was observed in 80.37% of the patients, in situ ductal carcinoma was observed in 11.21% infiltrating lobular carcinoma in 2%, in situ lobular carcinoma, cribriform, micropapillary, mucinous, intracystic papillary , papillary andinflammatory carcinoma was observed 1 case of each one. Two pregnant women were noted among the cases, and 6% of the patients had synchronous or asynchronous bilateral breast cancer. Both case and control patients started to wear bras around menarche (99%).

Crude prevalence ratio analysis revealed that the following covariates were not statistically associated with the occurrence of breast cancer according to the criterion pmenopause, family history of breast cancer, alcohol consumption, bra with a metal underwire, body mass index. However the bra-wearing time multiplied by the bra stretch percentage (p<0.0001), the brawearing time (p<0.0001) (Table 1), the cigarrete smoking (p<0.0001) and hormone replacement therapy (p=0.25) were transported to multivariate analyses.

| | Group* | | |

|---|

| Variables | Cases | Controls | p-value# |

|---|

| Stretchness x Time | | | <0.0001 |

| 1-150 | 33(22,52) | 69(45,39) | |

| 151-300 | 42(27,81) | 59(38,82) | |

| >300 | 75(49,67) | 24(15,79) | |

| BraDiameter | | | 0.1355 |

| ≤ 19 | 73(48,03) | 86(56,58) | |

| >19 | 79(51,97) | 66(43,42) | |

| Brawearingtime(Hours) | | | <0.0001 |

| ≤8 | 16(10,60) | 47(31,33) | |

| 9-16 | 66(43,71) | 92(61,33) | |

| >16 | 69(45,70) | 11(7,33) | |

*Values in frequency (%); #p-valor by chi square test

Table 1: Bra Stretch percentage X Time of use (h), Bra stretchiness percentage and Bra wearing time (Hours/day).

Subsequently, the multivariate analysis revealed that the frequency of cancer was 2.27-fold higher in patients where the bra wearing time multiplied by the stretch percentage was greater than 300 when compared to patients where this measurement was lower than or equal to 150 (p<0.0001). We also observed that the frequency of cancer was 2.79-fold higher in patients who wore bras more than 16 hours per day when compared to those who wore bras for less than or equal to 8 hours per day (p<0.0001). In contrast, the bra stretch percentage greater than 19 were not significant risk factors for cancer occurrence (p=0.3047) (Table 1).

Finally the results of our Poisson regression analysis also indicated a positive association between the bra-wearing time multiplied by the bra stretch percentage, the bra-wearing time (independent variables of interest) and cigarrete smoking. The frequency of cancer was respectively 1.78 and 1.49 -fold higher in patients who smoked compared to those who did not smoke (p<0.0001). However Hormone replacement therapy was not a significant risk factor for cancer occurrence in those patients (p=0.3109) and (p=0.3053) (Tables 2 and 3).

| | | PrevalenceRatio(95%CI) |

|---|

| Prevalenceofbreastcancer(95%CI) | Crude | p-value | Adjusteda | p-value |

|---|

| PercentagexTime(SxT) | | | <0.0001 | | <0.0001 |

| =150 | 37.04(24.01-50.07) | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| 150-300 | 54.79(17.71-39.86) | 1.17(0.74-1.86) | 0.5035 | 1.24(0.79-1.93) | 0.3465 |

| >300 | 81.39(69.63-93.16) | 2.20(1.51-3.20) | <0.0001 | 2.27(1.58-3.26) | <0.0001 |

| Smoking | | | <0.0001 | | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 81.82(65.51-98.12) | 1.75(1.33-2.29) | <0.0001 | 1.78(1.36-2.33) | <0.0001 |

| No | 46.87(38.13-55.62) | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| HRT | | | 0.2500 | | 0.3109 |

| Yes | 43.90(28.54-59.27) | 0.80(0.54-1.17) | 0.2500 | 0.83(0.59-1.18) | 0.3109 |

| No | 55.05(45.60-64.49) | 1 | - | 1 | - |

aAdjusted for percentage x time, smoking and hormone replacement therapy (HRT).

Table 2: Prevalence of breast cancer (%) and crude and adjusted prevalence ratios of the occurrence of breast cancer with bra-wearing time x stretch percentage according to the selected demographic, behavioural and clinical variables.

Discussion

This study is the first to investigate the degree of bra stretchiness multiplied by the number of hours per day that the patient wears this type of clothing. Previous studies only analysed the number of hours wearing a bra or investigated the bra cup size without directly measuring the fit [16,17]. We believe that the ideal is to evaluate these variables together because one variable depends on the other one to cause its effect. The multivariate analysis indicated that the SxT was an independent risk factor for breast cancer and was not affected by any of the other factors investigated (Table 2). In addition, wearing a bra for a long period of time was a significant risk factor for breast cancer (Table 3), which is in agreement with a previous study that found that premenopausal women who did not wear a bra had half the risk of developing the disease compared to those who wore it [17]. We also found an association in wearing a bra for a long period and breast cancer among pre- and postmenopausal women. Although Chen et al. did not observe this correlation in postmenopausal women [16], it is believed that it happen because those studies were performed with women of different socio-economic and educational level.

We also observed that women with breast cancer had the peculiar habit of frequently wearing a bra to sleep (36.84%), as opposed to those without the disease (7.23%) which was previously observed by Yao et al. [21]. It is especially difficult to dissociate the increased risk of wearing a bra to sleep from the increased proportional risk of wearing a bra for a longer period of time. Moreover it was noted that obese patients wearing more a bra to sleep (32.25%), than obese patients without the disease (10.52%). One possible interpretation for this association, if it is real, is that the constriction caused by a tight bra for a long period of time contributes to the development of the disease in addition to obesity itself [14]. In contrast, Japanese women when living in their country had a small incidence of breast cancer compared with Western women, which is attributed to their diet [22]; however, Japanese women usually do not wear bras as much as western women [17], which could be a factor that contributes to reduce the risk of the disease in this population. Regarding the degree of bra tightness, it was noted that patients with breast cancer wore tighter bras when compared with the controls; however, this difference was not significant (Table 1). We also observed that the metal underwire, which is considered a constricting element, did not correlate with the risk of breast cancer in the present study.

| | | PrevalenceRatio (95%CI) |

|---|

| | Prevalence (95%CI) | Crude | p-value | Adjusteda | p-value |

|---|

| Time | | | <0.0001 | | <0.0001 |

| ≤8 | 30.23(16.35-44.12) | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| 8-16 | 45.71(33.91-57.92) | 1.51(0.90-2.55) | 0.1197 | 1.52(0.92-2.52) | 0.1047 |

| >16 | 89.19(79.07-99.31) | 2.95(1.85-4.71) | <0.0001 | 2.79(1.77-4.41) | <0.0001 |

| Smoking | | | <0.0001 | | 0.0039 |

| Yes | 81.82(65.51-98.12) | 1.75(1.33-2.29) | <0.0001 | 1.49(1.14-1.96) | 0.0039 |

| No | 46.87(38.13-55.62) | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| HRT | | | 0.2500 | | 0.3053 |

| Yes | 43.90(28.54-59.27) | 0.80(0.54-1.17) | 0.2500 | 0.84(0.61-1.17) | 0.3053 |

| No | 55.05(45.60-64.49) | 1 | - | 1 | - |

aAdjusted for time x percentage, smoking and hormone replacement therapy (HRT).

Table 3: Prevalence of breast cancer (%) and crude and adjusted prevalence ratios of the occurrence of breast cancer with bra-wearing time according to the selected demographic, behavioural and clinical variables.

The mechanism by which a tight bra worn for several hours per day would lead to breast cancer is unknown; however, it is suggested that disease could develop via direct or indirect pathways. The bra is the only article of clothing that tightens the whole organ that it covers, and the repetitive and chronic direct trauma of this garment pressing all quadrants of the breast could lead to disease through the radial scars. The radial scars is a hyperplastic proliferative disease of the breast that is associated with a high risk of breast cancer. The chronic ischemia of the breast with subsequent slow infarction has been associated with those lesions [23]. In fact, radial scars were suggested to be related to the histogenesis of breast cancer and may be a precursor [24,25]. It has been postulated that the pathogenesis of those lesions arise as a result of unknown injury, leading to retraction and fibrosis and of surrounding breast tissue, thus performing a stellate configuration [26]. In addition, evidences indicates that they are an independent risk factor for the development of breast cancer, as they are associated with atypia and/or malignancy [27].

Another mechanism considered an indirect pathway is the blocking of substances. Kumar believes that the mammary gland is the only completely mobile structure in the female body, and restricting its mobility by wearing a bra would compromise its temperature and functioning [28]. More than 88% of breast drainage occurs via axillary lymph nodes [29]. When foreign substances (i.e., antigens) invade the body, antigenic material and cells that mediate the inflammatory response produced by the local immune activity at the aggression site are collected by all lymphatic vessels and transported into the lymph flow. The system of lymphatic vessels has been called an “information superhighway” because lymph contains a wealth of information about local inflammatory conditions in upstream drainage fields [30]. Bras and other external tight clothing can impede flow, cutting off lymphatic drainage so that toxic chemicals are trapped in the breast [31]. Several other risk factors for breast cancer were studied. Smoking was determined to be an important cause for the development of this disease. Despite being questioned and even denied by some [32], breast cancer due to smoking has been systematically confirmed in other studies [13,33]. Regarding the other studied variables associated with breast cancer risk, most were not significant in this group of patients. There are conflicting results regarding these factors in the literature, especially in studies conducted in developing countries and with poorer populations [15,34,35]. The variances observed in different studies may be due to socio-demographic, geographic and lifestyle differences and might also be due to recall bias, which is very common in case-control studies [15,35].

The present study had some limitations. The study represents a moment in time, and only the bra that the patient was wearing on the day of the interview was evaluated, although bra -wearing habits tend to be relatively stable over women’s lifetimes [16]. Moreover, the fact that the study was performed with women of lower socio-economic class was positive because these women very often reported not having many bras. Another observation is that the bra material does not always provide the same type of tightening over the breasts, although 85% of the women were wearing spandex bras and 15% were wearing cotton bras (data not shown). Future studies should be performed in laboratories to evaluate the level of pressure that each type of bra material exerts on the breast. Furthermore, there are not many studies about bra use and breast cancer risk, and thus additional larger and well-designed studies are needed.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated the existence of a relationship between the use of a tight bra when associated with an increased number of hours wearing it and the risk of breast cancer among pre- and post-menopausal women. This result was observed even after multivariate analysis was performed with confound factors. In addition, the study revealed new data that may help to better elucidate the risk factors for breast cancer and to prevent this disease, which has increasing incidence in developing countries [3,15,35] and is one of the biggest killers of women worldwide [1-3].

Authors’ Contributions

Comments

Post a Comment